THE ASIAN AFFAIRS PUBLISHER'S MOOD

Lies, damned lies and statistics

The twice Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli used to say: there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics. He would not be surprised to see us today, with our mega computers running the world, the banks and our democracies, deluged by statistics, with the sole purpose of hiding simple truth.

Take for example the current food crisis (or so-called food crisis). The sharp rise in food price is, we are told, the result of a deficit of production due to, guess, bio-fuel. Ethanol is one of the culprits. We are also told that the sharp rise in the price of oil is due to the scarcity of the product, and/or the appetite of China and India. And to back up such conclusion we are fed statistics.

But I have a problem with those numbers. They don’t add up. Take the price of rice. It has risen by 75% in nine months. And so has corn (the ethanol story) and eggs (what do we do with eggs?).

For Asia, rice matters for it is what Asian people eat. But do you think the price of rice is decided, say, in Vietnam, or in the Philippines, not to mention China? No, the price is fixed in Chicago. This is quite strange because the US accounts only for 2% of the world rice production.

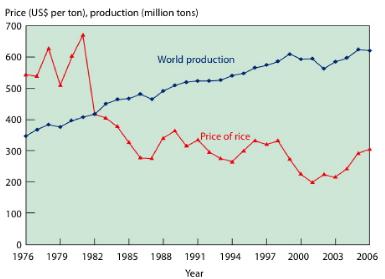

What I know about rice is that the world production was about 645 millions tons in 2007, against 395 millions in 2003. This is a 63% increase over 5 years. Meanwhile the population of the world, assuming we all consume rice, went from 6 billion to about 6.6 billion, an increase of about 10%. Then when we look at the trend for the past 30 years (see the chart) we get even more confused. The trend was down, which makes sense when we have an increase of production that is six times faster than the rate of increase in the population. Then the price of rice went up by 75%, in league with all other commodities in a matter of months.

Did we forget something? Yes, the price was in US dollars. If we were using a price deflator to take into account the downfall of the American currency, what would be the true value of the rice? This is a difficult exercise because we do not have a fixed Gold standard of some sort. Everything nowadays moves. We are on a slippery slope.

Say for the sake of argument that we express the price in the new currency that we never see in any world statistics, the euro. It is not that the euro does not exist but Europe does not print the euro to finance deficits. So you do not have Treasury bonds in euros that Japan or China could swallow.

The euro versus the dollar in a short seven years is a frightening story. At the launch of the euro (January 1999) the rate was fixed at 1.18. The euro rapidly tanked under unflattering commentaries from Wall Street analysts and traders. In October 2000, its exchange value was 82,305 cents.

See on the chart that at the time, the price of rice reached its lowest level of the past thirty years. Say it was at US$200 a ton (€242). Last year (2007) the average price was US$350, quite a substantial increase in US dollars over seven years, but expressed in euros the price would have been €240, which means no inflation over the period and no crisis. In 2008, the price jumped at US$500, at the peak of the so-called crisis (it has since then dropped back). At the 2008 exchange rate of the euro (at some point 1.5849), the price expressed in euros reached a peak of €315 (+ 30% over 8 years – an average of not even 3.5% compounded increase every year). A 3.5% price rise year on year is nothing to talk about. It does not bring a crisis – and yes, there is a financial crisis going on. So how can we trust statistics?

To get rid of the problem of currency, a Belgium economist, Philippe Defeyt, of the “Institut pour un développement durable” (Institute for a sustainable development) has recently tried to go away with the currency factor. He asked a simple question. How long would you have to work to purchase in 2007 some products that are part of your daily life (he selected thirteen o them)?

Take the oil crisis: how much do you need to work in 2008 to fill up the tank of your car with 40 liters of gasoline? In 1983, when the price of the barrel reached US$31.95 before going lower, you had to work 375 minutes to pay for it. In 2008, you have to work no more than 325 minutes (- 13.3%). So in short, if the measure of price is working time, we pay less today than yesterday, even though we are told oil has never been so expensive and it is the end of the world. Philippe Defeyt does not even consider another factor: the fact that with a 40 liters tank a car runs twice the number of miles. So oil is ultimately cheaper than before when converted in man/hours, which after all is the ultimate currency because we have a limited span of time in our life.

Of course the answer does not apply to all countries but to the Euro economic zone only. Yet keep in mind that the Euro economic zone is now larger than the US economy, another fact that is conveniently ignored by the American media and the Wall Street traders.

What do all those numbers teach us and why are we so confused? First it is that statistics are not to be trusted. It is not that what they deliver is false, it is that the sampling procedure, which is at the heart of the greater part of statistics, is subject to all sorts of refinements. Those refinements are highly suspect. As the great Darrel Huff said many years ago in a wonderful little opus (How to lie with Statistics), the sample has most often than not a built-in bias. Today the built-in bias is the value of the dollar. Second, it is that there is no absolute crisis and that the price of oil or rice is not sustainable, as it is not attached to any real tangible measure such as the volume of production and the volume of consumption.

So what is going on? Maybe we should look at the issue from a different perspective, that of the Chicago traders. It is now admitted that the volume of trading in the commodities market has no relation with the volume of goods to trade.

If the volume of rice production has increased by 63% in five years, one might expect that the volume of transaction on the market has eventually increased in parallel. Allowing for inflation and speculation, one might even tolerate a slight divergence, say, from 63% to 100% (that divergence would represent a 50% increase in speculative activities). But what is the real number for such a divergence? It is more than a thousand times. This is because hedge funds using borrowed money and leveraging the borrowed money (which is tantamount to print money) have been betting more and more money on future contracts.

What is a future contract? It is one in which one party agrees to buy or sell a certain commodity, such as a ton of rice or a barrel of oil, at a certain price at an agreed upon date in the future. Those contracts have swelled to unprecedented numbers.

So here we are: on the one hand we have at best a 63% increase in volume, while we have speculators betting about 1000 times more on that volume. No wonder prices have gone mad. Academics long argued that future trading diminishes extreme price swings and volatility. But when an institution such as Lehman Bothers admits that it had leveraged hundreds of times one of its funds investing in that kind of shenanigans, academics have to recognized that future trading is just a way to print money in disguise.

What next? It is hard to guess but history tells us that what goes up must go down. And when you print money, you destroy your money. Every little duke or king has done it out of desperation in the Middle Age. The Bush administration has done it year after year – to pay for the Iraq disaster. Lastly the Fed, to save the gamblers, has borrowed between January 2008 and April 2008 US$335 billion. The amount has no precedent. Since 1919, the peak of borrowing has never been more than US$30 billion for a complete year, and the average has rather been a lowly 10 billion a year.

The payback is now: the dollar has lost not only its shine but also its substance and its reason. Ultimately, it is the end of the Bretton-Woods II world of the dominance of the dollar over the world economy. But we do not know what the consequences are going to be. We only know two things: a massive currency realignment of the currency game over the coming years is inevitable, and the current international financial architecture is crumbling. Banks are in big trouble and so are we. The politicians have not yet a clue about what is going on. They follow an old script, while we are witnessing a new play. The FED is printing money faster than ever, US banks are collapsing one after the other, requesting massive cash infusion in a devalued currency.

August 31, 2008

| |||